By Geeta Seshu

Our Pictures, Our Words by Laxmi Murthy and Rajashri Dasgupta, is a graphic history of protest, struggle, and solidarity in the women’s movement.

Around 25 years ago, a woman’s rights activist took my hand, more used to banging on a typewriter, and dipped it into a bucket of gum, playfully telling me, “now that you are an activist, you had better learn to stick a poster properly!”

The occasion was a demonstration in Mumbai’s Vile Parle against the sati incident in Deorala. As vividly as I still remember my first demo and Flavia Agnes – the feminist lawyer who started out by fighting her own battle against violence – showing me how to smear the gum on top of the poster so it would soak into the wall and remain there forever, I cannot for the life of me remember the poster I struggled to smear gum on.

The incident came back to me as I feasted on “Our Pictures, Our Words – A visual journey through the women’s movement’, with such a valuable collection of posters and photographs of so many years of struggle. Like Flavia’s simple act of instruction, it is a collection of memories and perspectives that can safely be handed over to a younger audience.

Zubaan’s poster project – 1200 posters and still counting – is a vital record of the struggles and debates that marked more than a quarter century of the myriad issues and concerns of the contemporary women’s movement in India. There must be literally thousands of posters that just drifted away with the wind but at least we have these painstakingly preserved archives. And now, with this book by Laxmi Murthy and Rajashri Dasgupta, we also have the context in which the posters made their statements.

Billed as an educational tool, the book examines patriarchy and the violence of subordination. Divided into four sections, it looks at the politics of the body – of rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment; health and desire; at the domination of the community – of religion and personal laws, honour killing and religious extremism; at societal politics – the denial of political participation and citizenship and governance and lastly, at the politics of access to the environment and land and the ‘invisibilisation’ and exploitation of women’s labour.

To cram in all of this in an ‘educational’ book is a tall order indeed and the book seems to groan under the weight of all that text. Other books (A history of doing by Radha Kumar; The Issues At Stake: theory and practice in the contemporary women’s movement in India, Nandita Gandhi and Nandita Shah; Fields of protest, Raka Ray – to name just a few) have tried to grapple with the myriad issues raised by the women’s movement. To make the issues more accessible and comprehensible to a younger audience is a challenge indeed.

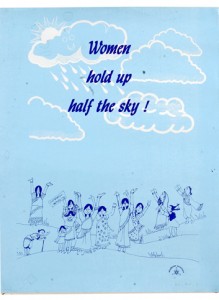

Taking the visual route is a wonderful way to do so. Throughout, the posters and pictures illustrate and bring to graphic life what may seem like a grim tale of the control and subordination of women and the violence and denial of women’s rights. What the posters and pictures do is provide a face to the anger. Look closely at the powerful “Indian Army Rape Us” picture of the ‘nude’ protest of the Meira Paibas in Manipur; the brown and black poster of a woman breaking off her shackles (Shramjeevee Mahila Samity, Kolkata), or the scream of the woman strangled by religion (Sheba Chhachi and Jogi Panghaal for Saheli).

The visuals also do what the songs of the women’s movement did – uplift and celebrate the unity and solidarity of women, their strength and spirit. So even as Laxmi Murthy and Rajashri Dasgupta examine the posters and how they depict the issue at hand (for example, the opening passage in the section on domestic violence is a gentle reminder that the early years of the women’s movement emphasized the ‘victim’ status of the woman with depictions of the drops of tears and blood and the downcast look ), they also pick up posters that celebrate – from the earlier posters of women streaming out of factories and fields to the later posters on sexuality and diversity.

The book does, alas too briefly, examine the image itself. Why were the women drawn in the way they were – ‘as sari-clad, long-haired, buxom and fair’ women and as dark-skinned, barefoot rural counterparts? Why were such few ‘urban’ women depicted in the posters – the short-haired women who were the bane of Janata Dal leader Sharad Yadav? How did posters from the NGOs with their development agendas depict women and women’s issues?

It also does not discuss the manner in which these posters came to life, the discussions and ideas of women’s groups or individual artists and illustrators who were roped in, often making posters even as the protest was underway, cutting out or retaining something and even the ownership or copyright issues that have cropped up with some posters or the fact that in so many of the posters, ‘ownership’ simply didn’t matter. That does tell you another tale of the women’s movement and one hopes another edition will redress these gaps.

Geeta Seshu is a Mumbai-based independent journalist who obsesses about media representation of women, freedom of expression, media literacy, the women’s movement and all else besides!